This week’s Ramblings are taking a look at inflammation of the heart – a subject, along with sepsis, that is close to my heart – apologies for the pun – but you generally get that when a family member personally experiences a disease – presenting with an altered GCS with cardiomyopathy (ejection fraction of 30%) believed to be caused by myocarditis.

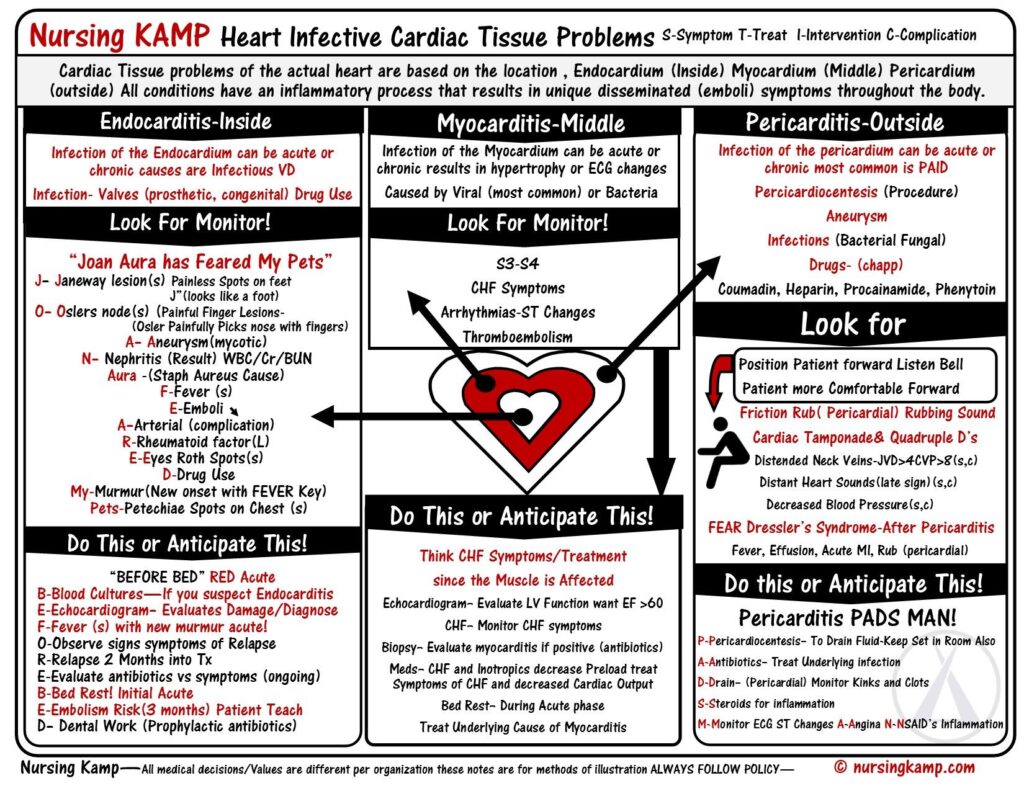

There are three main types of heart inflammation: endocarditis, myocarditis, and pericarditis. While all are caused by inflamed tissues, their presentation, severity and management varies.

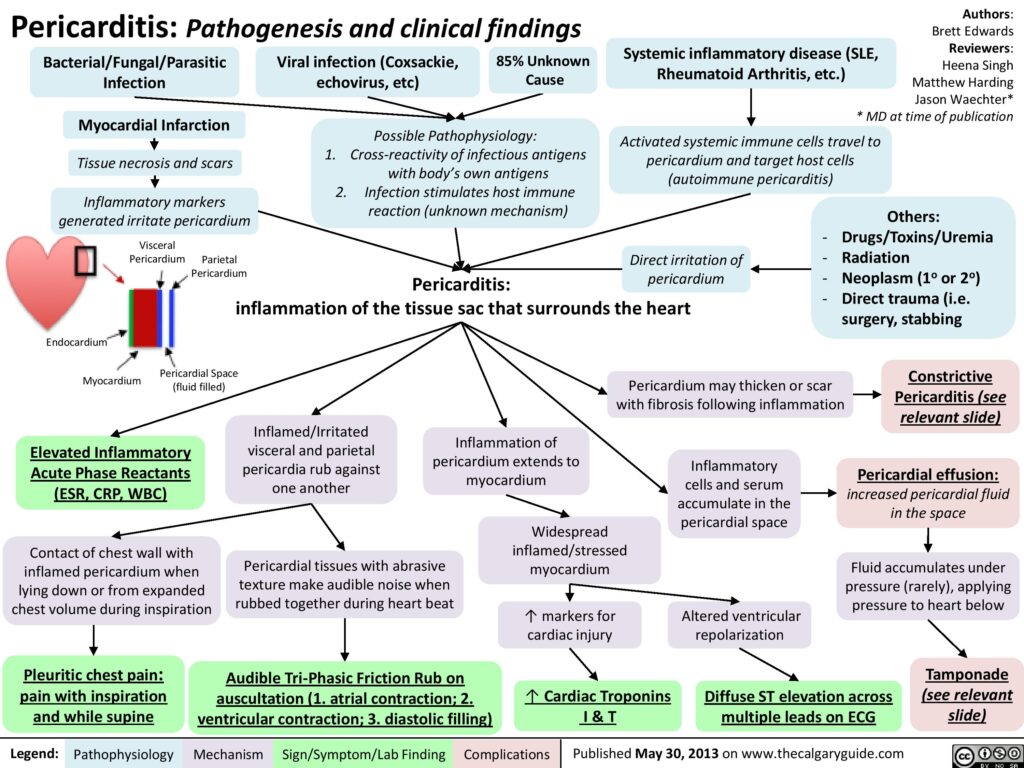

Pericarditis

Pericarditis is a condition in which the pericardium — the sac surrounding the heart — gets inflamed. This sac is made of two thin layers of tissue with a small amount of fluid in between. The fluid keeps the layers from rubbing against each other and causing friction. The pericardium holds the heart in its position in the chest and protects it from infection.

Pericarditis accounts for approximately 5% of all causes of chest pain presenting to the ED. Acute pericarditis may be complicated by the development of a pericardial effusion that, if significant enough to compress the cardiac chambers, may produce cardiac tamponade. More than 80% of cases of acute pericarditis are idiopathic (unknown) or presumably viral in origin.

Inflammation of the pericardium produces characteristic chest pain (sudden, sharp, retrosternal, pleuritic, worse on lying flat, relieved by sitting forward), tachycardia and dyspnoea. Patients frequently also present with fever, malaise and myalgias (muscle aches) in association with their chest pain. There may be an associated pericardial friction rub or evidence of a pericardial effusion. Widespread ST segment changes occur due to involvement of the underlying epicardium (i.e. myopericarditis – inflammation of the pericardium and myocarditis).

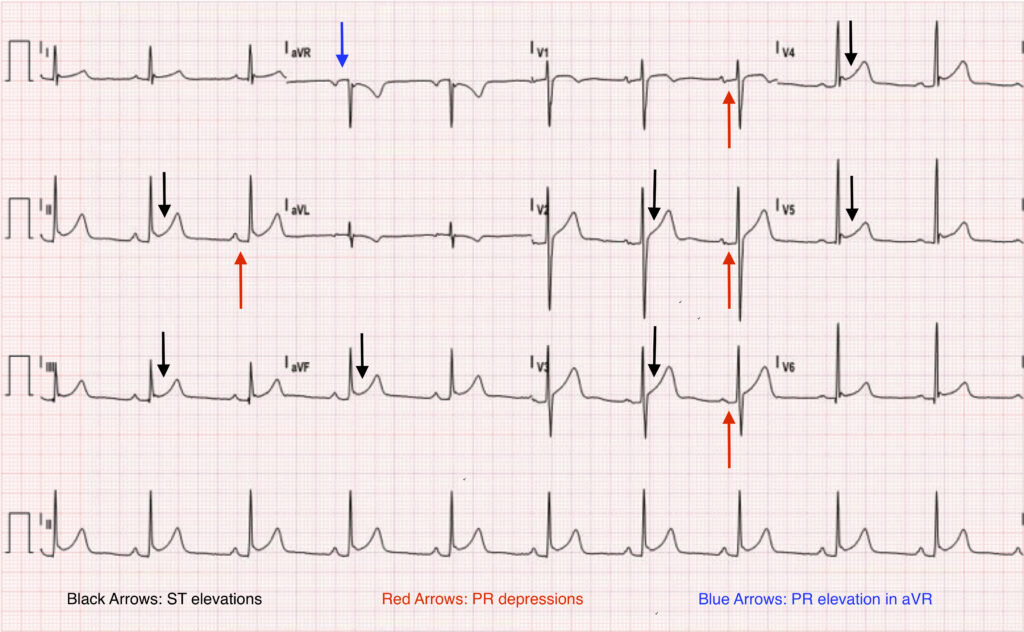

Electrocardiography is often diagnostic for acute pericarditis. While the pericardium itself is electrically inert, epicardial (inner layer of the pericardium) inflammation from an overlying pericarditis progresses through four classic stages.

- Stage 1 is marked by diffuse, upward concave ST-segment elevations with reciprocal ST-segment depressions in aVR and V1. PR-segment depression may be seen in most leads with the exception of aVR and V1 (see attached ECG).

- These changes are seen within the first hours of initial symptoms and may last up to two weeks before returning to baseline, defined as stage 2.

- As inflammation and injury progresses into the second and third weeks, stage 3 is characterised by diffuse T-wave inversions.

- Stage 4 marks the resolution of these T-wave inversions, though some may persist indefinitely.

The mainstay of treatment for acute pericarditis is pain relief and resolution of inflammation. When no contraindications exist, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended – however, pericardial infusions and cardiac tamponades may need draining. Pericardial effusion is seen in approximately 60% of acute pericarditis cases, but cardiac tamponade is more uncommon and occurs in approximately 5% of cases. A classical clinical feature is ‘Beck’s triad’ – hypotension, elevated JVP and muffled heart sounds. Other features include tachypnoea, tachycardia and atrial arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation, pulsus paradoxus, Kussmaul sign (a paradoxical rise in JVP on inspiration), weakened peripheral pulses, peripheral oedema and cyanosis.

Further reading on pericarditis:

https://www.racgp.org.au/afp/2017/november/pericarditis/

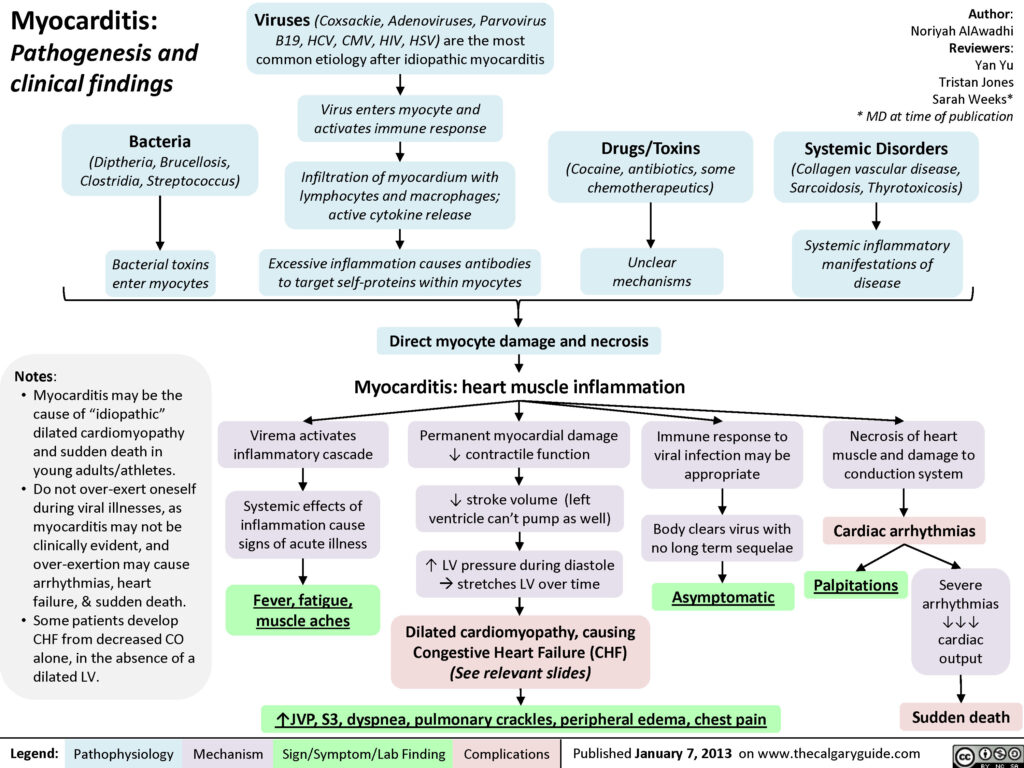

Myocarditis

Myocarditis is an uncommon disease marked by inflammation myocardium and other changes to the heart muscle cells that may be acute or chronic. Myocarditis can affect small or large sections of the heart muscle, making it harder for the heart to pump blood, which in turn can lead to heart failure.

In the acute setting myocarditis can cause arrhythmias, cardiac failure, cardiogenic shock and death – it is a commonly recognised cause of sudden unexplained cardiac death in young adults. Depending on the degree of injury, myocarditis may also be complicated by dilated cardiomyopathy (enlarged heart which cannot pump blood effectively) and left ventricular dysfunction.

The clinical presentation of myocarditis is highly variable. While some patients may be completely asymptomatic, others present acutely ill with fever, chest pain, myalgias (muscle aches), arthralgias (joint pains), exertional dyspnoea, palpitations and syncope. In many cases, these symptoms may be preceded by a nonspecific viral prodrome (early sign or symptom) of respiratory and gastrointestinal complaints as well as fever, malaise and headache. Some may also present with symptoms consistent with acutely decompensated heart failure and hemodynamic collapse, suggesting progression to cardiomyopathy. Auscultation of the chest might reveal a third or fourth heart sound, a new heart murmur, or evidence of pulmonary congestion, all suggestive of heart failure.

Electrocardiographic changes frequently seen in myocarditis are consistent with acute injury or ischemia and may in many instances be mistaken for acute myocardial infarction. ST-segment elevation and depression, T-wave inversions and pathologic Q-waves have all been seen in cases of myocarditis where myocardial infarction was initially suspected and coronary angiography was subsequently normal. Ventricular arrhythmias and heart block may also manifest with myocarditis and cardiomyopathy, however, the most common abnormality seen in myocarditis is sinus tachycardia with non-specific ST segment and T wave changes.

Treatment is supportive, aimed at promptly recognising and treating cardiac arrhythmias, preserving myocardial function, and preventing heart failure and other complications, such as dilated cardiomyopathy. Mainstays of treatment include providing supplemental oxygen, limiting myocardial oxygen demand, and enhancing circulatory support and cardiac output if needed.

Further information on recognising and managing myocarditis can be read at:

https://journals.lww.com/nursing/Fulltext/2004/04000/Recognizing_and_managing_myocarditis.31.aspx

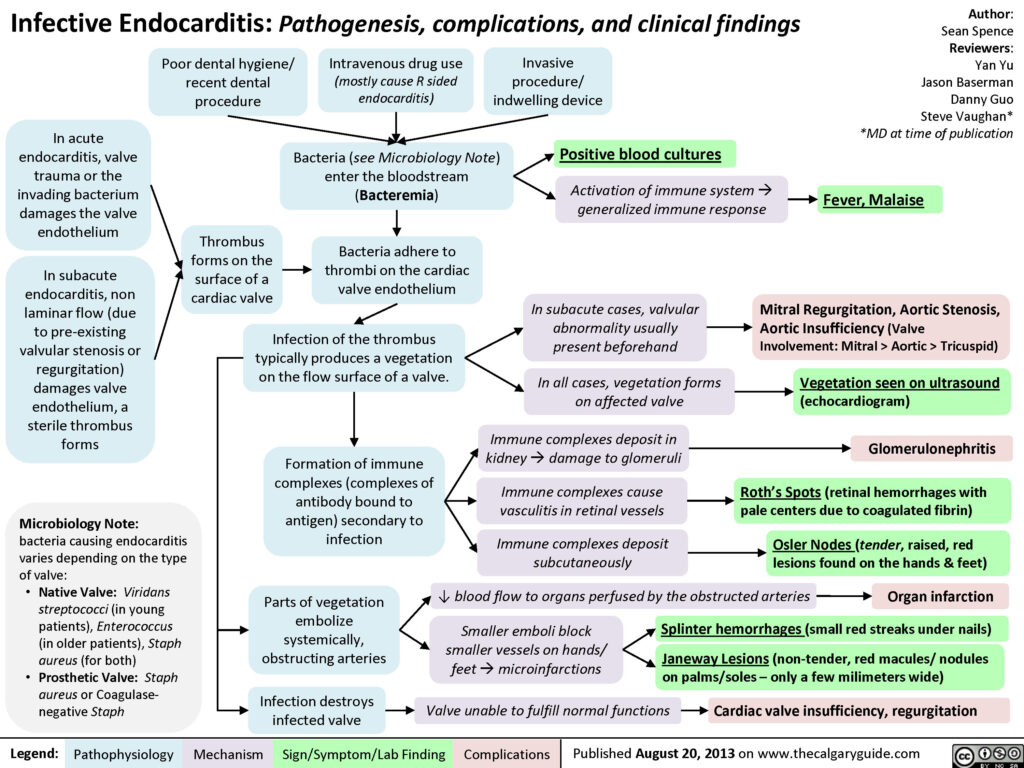

Endocarditis

Endocarditis is inflammation of the inner lining of the heart chambers and valves, or endocardium. Endocarditis is a rare but life-threatening disease. In endocarditis, clumps of bacteria or fungi, along with blood cells, collect on the endocardium. These clumps occur more often on the heart valves than on the heart chambers. Pieces of these clumps can break off and travel to different parts of the body, blocking blood flow or spreading infection.

Fever remains the most common clinical presentation of infective endocarditis – it may exceed 40º C in cases of acute infective endocarditis and can be accompanied by chills and rigor. However, it may also be absent in the elderly and in patients with congestive heart failure, chronic renal failure or liver disease. Systemic symptoms such as myalgias (muscle aches), fatigue, malaise, night sweats, anorexia, nausea and vomiting may be seen and often predominate in subacute presentations. Up to 10% of patients with infective endocarditis may report chest pain.

Endocarditis should be suspected in any patient with unexplained fevers, night sweats, or signs of systemic illness, particularly if any of the following risk factors are present: a prosthetic heart valve, structural or congenital heart disease, intravenous drug use, and a recent history of invasive procedures (e.g., wound care, hemodialysis). Other symptoms can include splinter haemorrhages under the fingernails, Janeway lesions (small non-painful lesions on the palms or soles), Osler’s nodes (small painful lesions on the fingers or toes) or finger clubbing.

Many cases of endocarditis are successfully treated with antibiotics. Sometimes, surgery may be required to fix damaged heart valves and clean up any remaining signs of the infection.

Further information can be found here:

The following article discusses possible etiologies for fever and chest pain:

http://www.antimicrobe.org/new/printout/e39printout/e39card.htm

Also beware that patients who are immunocompromised or have auto-immunise diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis or SLE (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus – which deserves its own Rambling feature – a job for a different day), can increase the likelihood of inflammatory heart diseases. For further reading on how Lupus can affect the heart and the circulation can be found here:

https://www.lupus.org/resources/how-lupus-affects-the-heart-and-circulation

During the last couple of weeks I have had several questions about referencing the Ramblings for CPD purposes, especially the difficulties linking to closed groups. To make this easier I have uploaded previous Ramblings to one of our (almost) dormant websites (too many projects, too little time!) and will add further Ramblings as they are published – the address is:

https://www.paramedicine.education/category/ramblings-red-shift/

This way the article can be linked directly or referenced using the following format – yes, it’s in Vancouver referencing style but after my Master of Health Professions Education thesis it’s the only style I can remember: PaReflectionEd [Internet]. Perth WA: PaReflectionEd; c2016-2020. Title of article; Date of publication [cited (date you read the article)]. Available from: https://www.paramedicine.education/(title of article)/