It’s always nice when you have confirmation that your provisional diagnosis was correct. While we can simply treat abdominal pain by managing the symptoms – namely anti-emetrics for nausea and vomiting, analgesia for pain and fluids for hypotension, personally I like to try to work out what could be the possible cause of my patient’s symptoms. A couple of weeks ago we attended the home of a 7-year old patient who had just had a seizure of unknown cause. While talking to the daughter – who was sulking because she didn’t want to go to hospital – her mother said that we had recently attended to her for abdominal pain – what we thought was cholecystitis – and that she subsequently had her gall bladder removed. So the Ramblings this week are taking a look at acute cholecystitis, a common cause of right upper quadrant abdominal pain.

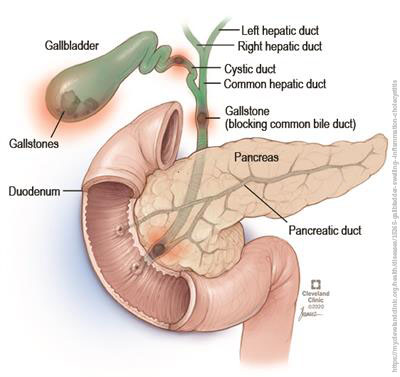

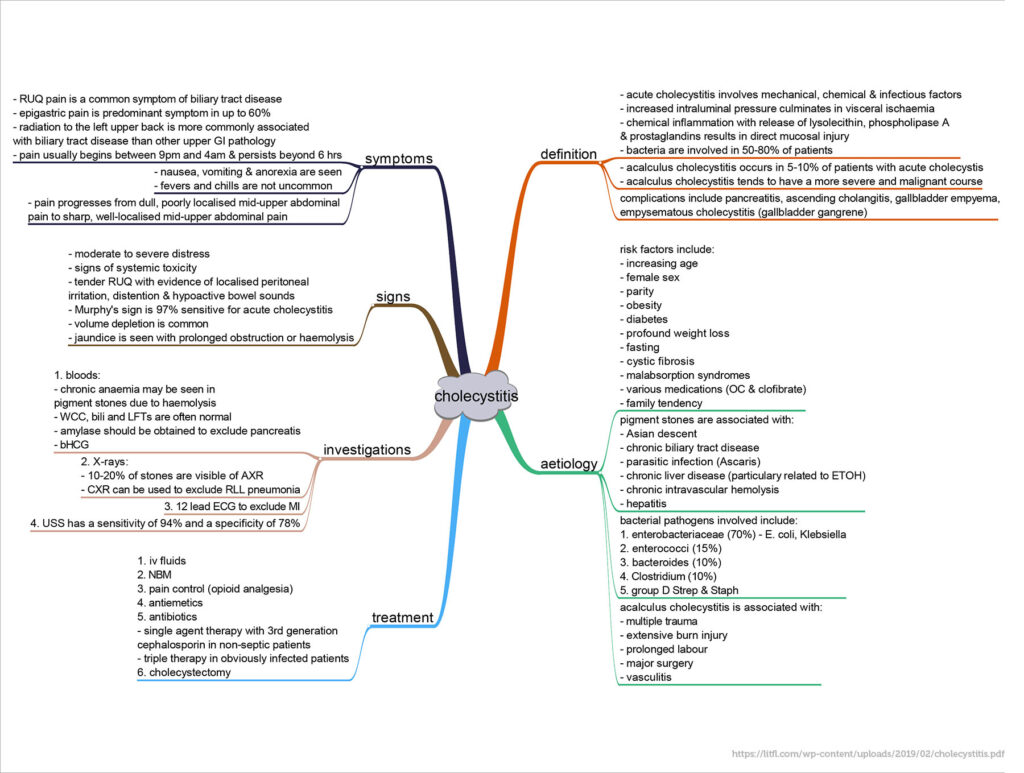

Acute cholecystitis is inflammation of the gallbladder that develops over hours, usually because a gallstone obstructs the cystic duct. The gallbladder is a small organ underneath the liver on the right side of the upper abdomen. It stores a thick dark green fluid called bile which the liver produces to help with digestion. This results in a build-up of bile, which causes inflammation. Untreated, it can result in perforation of the gallbladder, tissue death and gangrene, fibrosis and shrinking of the gallbladder, or secondary bacterial infections.

The acute onset of severe right upper quadrant pain most commonly is associated with the presence of gallstones. Between 10-15% of males and 20-25% of females of all ages have gallstones and the incidence of symptoms developing in asymptomatic patients is between 1-2% per annum.

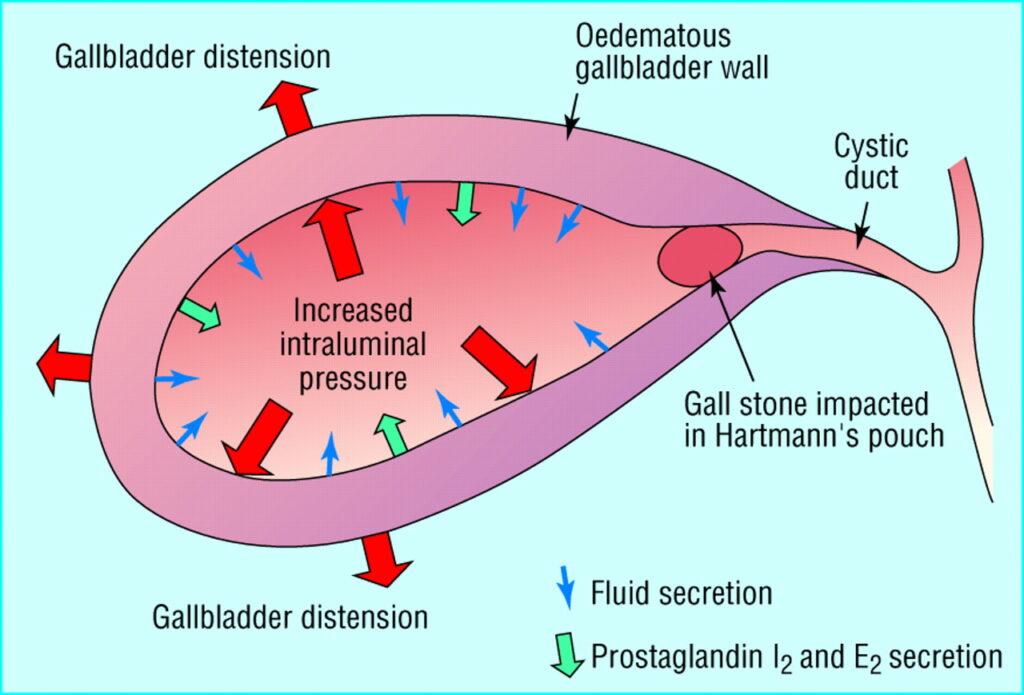

Acute cholecystitis is the most common complication of cholelithiasis (formation of bile stones). In fact, almost all patients (≥ 95%) with acute cholecystitis have cholelithiasis. When a stone becomes impacted in the cystic duct and persistently obstructs it, acute inflammation results. Bile stasis triggers release of inflammatory enzymes (eg, phospholipase A, which converts lecithin to lysolecithin, which then may mediate inflammation). The damaged mucosa secretes more fluid into the gallbladder lumen than it absorbs. The resulting distention further releases inflammatory mediators (eg, prostaglandins), worsening mucosal damage and causing ischemia, all of which perpetuate inflammation. Bacterial infection can supervene. The vicious circle of fluid secretion and inflammation, when unchecked, leads to necrosis and perforation. If acute inflammation resolves then continues to recur, the gallbladder becomes fibrotic and contracted and does not concentrate bile or empty normally – features of chronic cholecystitis.

Cholecystitis can also be caused by other problems with the bile duct, such as a tumour, problems with blood supply to the gallbladder, fibrosis, lymphadenopathy (disease of lymph nodes) and parasitic infections. There are also two less common, but more serious, variant forms of cholecystitis:

- Acalculous cholecystitis is inflammation of the gallbladder in the absence of gallstones or cystic duct obstruction. It is more common in older patients and occurs after non-biliary tract surgery, accounting for 5 to 10% of cholecystectomies done for acute cholecystitis. The symptoms are similar to those of acute cholecystitis with gallstones but may be difficult to identify because patients tend to be severely ill and may be unable to communicate clearly. Abdominal distention or unexplained fever may be the only clue. Untreated, the disease can rapidly progress to gallbladder gangrene and perforation, leading to sepsis, shock, and peritonitis, with mortality approaching 65%.

- Emphysematous cholecystitis (1% of cases): Inflammation of the gallbladder along with the presence of gas in the gallbladder wall. It is more commonly seen in diabetic patients. This gas, emitted by bacteria, is thought to result from gallbladder ischemia caused by vascular compromise with subsequent bacterial invasion. It has a high risk of perforation, gangrene and sepsis.

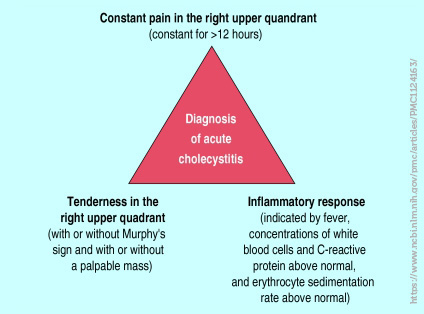

Most patients have had prior attacks of biliary colic or acute cholecystitis. Typical clinical features include right upper quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting, tachycardia and sometimes a pyrexia. Tenderness may also be present on examination in the right upper quadrant. Pain may radiate around the waist or to the left upper back, often occurring between 9pm and 4am. The pain of cholecystitis is similar in quality and location to biliary colic but lasts longer (ie, > 6 hours) and is more severe. Within a few hours, the Murphy sign (deep inspiration exacerbates the pain during palpation of the right upper quadrant and halts inspiration) develops along with involuntary guarding of upper abdominal muscles on the right side. The finding of right upper abdominal pain with deep palpation, Murphy sign, is usually classic for cholecystitis. Often, there is also a specific dietary event leading to the acute attack, such as “I ate pork chops and gravy last night.”

Murphy’s sign is elicited in patients with acute cholecystitis by asking the patient to take in and hold a deep breath while palpating the right subcostal area. If pain occurs on inspiration, when the inflamed gallbladder comes into contact with the examiner’s hand, Murphy’s sign is positive. A video on identifying a positive Murphy’s sign can be found here:

Identifying a positive Murphy’s sign is one element of an abdominal assessment that is easy to perform, similar to how rebound tenderness (Blumberg sign) is suggestive of peritonitis, and can be useful in developing a differential diagnosis of the patient’s abdominal pain. The first video describes undertaking an abdominal assessment while the second looks at an approach to acute abdominal pain:

The differential diagnosis of acute cholecystitis are:

- Appendicitis;

- Biliary colic (pain from gallstone blocking cystic duct);

- Cholangitis (inflammation of bile duct system);

- Mesenteric ischemia (insufficient blood supply to small intestine)

- Gastritis (inflammation of the lining of the stomach);

- Peptic ulcer disease.

In patients with superimposed bacterial infection, septicaemia develops and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Patients with severe acute cholecystitis may have mild jaundice caused by inflammation and oedema around the biliary tract and direct pressure on the biliary tract from the distended gall bladder. In older patients, the first or only symptoms may be systemic and nonspecific (eg, anorexia, vomiting, malaise, weakness, fever). Sometimes fever does not develop. Risk factors include:• increased age;• female;• parity;• obesity;• diabetes mellitus;• profound weight loss;• fasting;• cystic fibrosis;• malabsorption syndromes;• familial;• various medication (oral contraceptive pill and clofibrate).

Uncommonly, acute cholecystitis may present even if the patient has had a cholecystectomy.As with other medical complaints, acute cholecystitis can have additional complications. Without treatment, 10% of patients develop localised perforation, and 1% develop free perforation and peritonitis. Increasing abdominal pain, high fever, and rigors with rebound tenderness or ileus suggest empyema (pus) in the gallbladder, gangrene, or perforation. When acute cholecystitis is accompanied by jaundice or cholestasis, partial common duct obstruction is likely, usually due to stones or inflammation. Other complications include the following:

- Mirizzi syndrome: Rarely, a gallstone becomes impacted in the cystic duct and compresses and obstructs the common bile duct, causing cholestasis;

- Gallbladder perforation. The gall bladder is perforated in 10% of cases of acute cholecystitis – usually in patients who sought medical attention after a delay or in those who do not respond to conservative management. Perforation most commonly occurs at the fundus. After the gall bladder has perforated, patients may experience transient relief of their symptoms because the gall bladder decompresses, but peritonitis then develops. Free perforation presents with generalised biliary peritonitis and is associated with a mortality of 30%;

- Gangrenous cholecystitis. Gangrenous cholecystitis occurs in 2-30% of cases of acute cholecystitis. Men aged over 50 with a history of cardiovascular disease and leucocytosis have the highest risk of gangrene of the gall bladder;

- Gallstone pancreatitis: Gallstones pass from the gallbladder into the biliary tract and block the pancreatic duct;

- Cholecystoenteric fistula: Infrequently, a large stone erodes the gallbladder wall, creating a fistula into the small bowel (or elsewhere in the abdominal cavity); the stone may pass freely or obstruct the small bowel (gallstone ileus).

In a pre-hospital treatment, management is largely supportive care and transportation to an appropriate emergency department. First priority is assessing whether the patient is stable – if not, initiate resuscitation and consider the presence of sepsis. Also consideration of other life threatening diagnoses, including acute pancreatitis, septic shock from other intraabdominal source or right sided pneumonia, perforated viscus (in particular perforated peptic ulcer, ruptured ectopic pregnancy in women of childbearing age) and cardiac ischaemia is appropriate. After initial assessment and examination, remembering that a positive Murphy’s sign is 97% sensitive and 48% specific for cholecystitis and to also perform an ECG to exclude cardiac ischaemia, care is focussed on maintaining hydration, anti-emetics and pain control.

Video:

Podcast:

References:

https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/cholecystitis-gallbladder-inflammation

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/172067#symptoms

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1124163/

https://litfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/cholecystitis.pdf

https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/173885-overview

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15265-gallbladder-swelling–inflammation-cholecystitis