This week’s Ramblings take a look at angioedema in patients taking ACE-inhibitors – a rare but potentially life-threatening presentation. While angioedema is a self-limiting localised subcutaneous (or submucosal) swelling which results from extravasation of fluid into the interstitial tissue, it can be life-threatening.

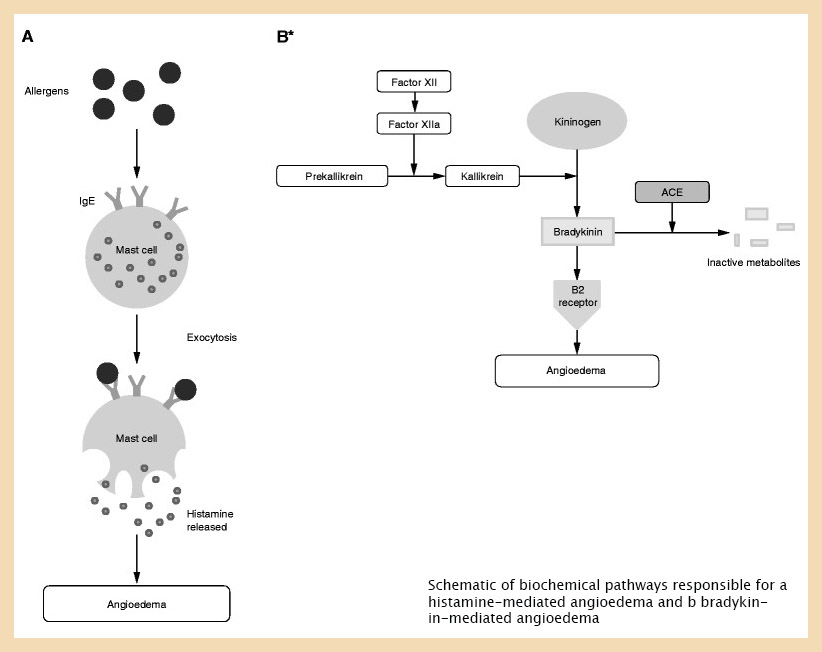

Allergic or hypersensitivity reactions are the most common cause of angioedema, triggers include: medications (e.g. NSAIDs, penicillins and other antibiotics); food (peanuts, shellfish, strawberries); envenomation (wasps, bees or other insects); or latex. This reaction is Immunoglobulin E-mediated and histamine induced, with patients often responding well to adrenaline, anti-histamines and corticosteroids. In these cases, angioedema may present as a component of anaphylaxis.

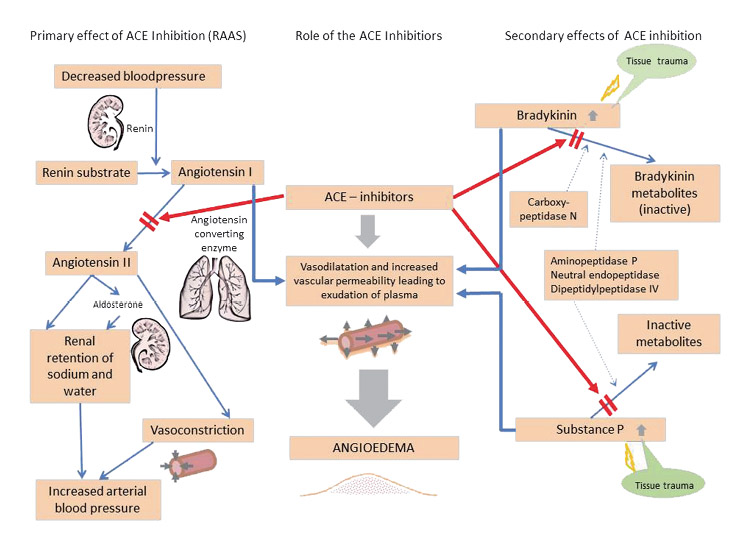

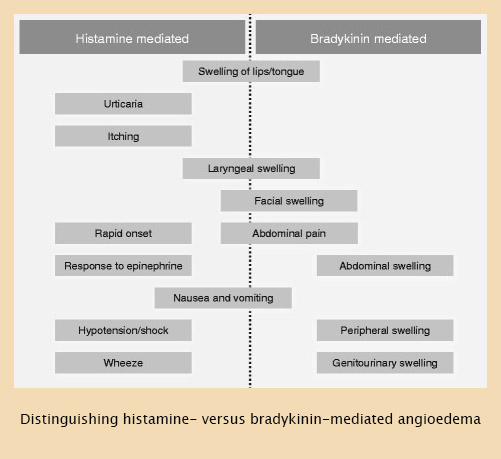

In non-allergic angioedema, bradykinin (an inflammatory vasoactive peptide) is produced in large amounts, which leads to increased vascular permeability and vasodilation that induces angioedema. Non-allergic angioedema is a less common presentation and does not have associated allergic features, such as urticaria (hives) or bronchospasm and does not usually respond to adrenaline, anti-histamine and corticosteroid treatments. Causes include:

- Hereditary angioedema – due to hereditary C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency or dysfunction;

- Acquired angioedema – due to acquired C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency; and

- ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme)-inhibitor induced angioedema.

Introduced in 1981 for the treatment of hypertension and congestive heart failure, ACE inhibitors – drug names ending in -pril such as Enalapril, Perindopril and Ramipril – have become one of the most largely prescribed medications worldwide. They work by causing relaxation of the blood vessels and a decrease in blood volume. While angioedema is a well-recognised side effect of these medications, with the reported incidence of ACE inhibitor angioedema ranging from 0.1% to 1.0%, its presentation is still confused with allergic or anaphylaxis reactions.

It is important to recognise that ACE inhibitor angioedema is a class effect and is not dose-dependent. Symptoms can occur anywhere from a few hours up to 10 years after the initial dose. In fact, up to 40% of patients with ACE-inhibitor angioedema present months to years after their initial dose. Swelling usually develops over minutes to hours, peaks, and then resolves over 24 to 72 hours, although complete resolution may take days in some cases. If the ACE inhibitor is not discontinued, the episode will still resolve, although the frequency and severity of future episodes appears to escalate, and the condition can become life-threatening.

Usually, ACE-inhibitor–induced angioedema presents itself as swelling without urticaria, most prevalent in the face, lips, tongue, the floor of the mouth, and the upper airways, leading to hoarseness, inability to swallow, and difficulty of breathing. Other manifestations of angioedema, such as gastrointestinal or genital swellings, are rarely caused by ACE inhibitors.

Several signs and symptoms indicate oedema in the upper airway, such as increased breathing frequency, use of accessory muscles of respiration, audible breathing, or even stridor. Asphyxiation is the leading cause of mortality in these patients, necessitating airway evaluation. As the oxygen saturation will deteriorate only in the later stages of respiratory failure, it is dangerous to rely on a good saturation reading alone to determine patient severity. While swelling of the lips and/or mucosa in the oral cavity is usually harmless in this respect (given that the patient is able to breathe through the nose), oedema of the pharynx and especially larynx is potentially life-threatening and rapid transportation to hospital should be considered.

Hospital treatment of patients with ACE-inhibitor angioedema focuses on discontinuation of the drug, airway management, and supportive care. Careful airway management is crucial with potential indications for intubation including stridor, dyspnoea, inability to manage secretions, progressive deterioration of oedema and significant laryngeal oedema. Angioedema can progress rapidly within hours, and airway obstruction occurs in up to 15% of patients with angioedema. The presence of epiglottic, aryepiglottic, or laryngeal oedema suggests the need for a definitive airway – the presence of laryngeal oedema is associated with a 25-40% mortality. If the angioedema exclusively involves structures anterior to the teeth such as the lips, intubation is generally not needed.

However, airway management is fraught with danger as airway manipulation may worsen the swelling. If stable and cooperative, awake fiberoptic intubation (AFOI) with anaesthetist and ENT involvement is preferred – awake intubation in a spontaneous breathing patient avoids loss of pharyngeal tone and can be performed in an upright position, both of which lessen the likelihood of airway compromise, however, even with advanced fiberoptic or video techniques it may be impossible to pass and endotracheal tube through the glottis due to swelling and failed attempts at intubation may worsen airway compromise.

If unstable with hypoxia and progressive airway obstruction, then laryngoscopy with a ‘double setup’ emergency surgical airway should be attempted – the team prepares for a cricothyrotomy before starting the intubation attempt. In these situations video laryngoscopy and the use of a bougie are preferred – supraglottic airway devices are more likely to fail due to the soft-tissue swelling and airway obstruction and an emergency surgical airway may be difficult due to distortion of anatomy and subcutaneous oedema (an extended vertical incision may be required initially). Ketamine-dissociated cricothyrotomy is another suggested approach for the crashing patient who is at immediate risk of losing their airway – thankfully this is a rare presentation. For patients with angioedema who require a definitive airway, cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy is needed in up to 50% of cases.

Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation can also assist with temporisation; however, this is not a definitive therapy for patients with airway involvement. Supraglottic and extraglottic airway devices are not recommended in patients with angioedema, as the device will remain above the site of airway obstruction. If placed, these devices may also worsen oedema due to the associated trauma with placement.

More recently, IV tranexamic acid has been used as a front-line emergency therapy to reverse episodes of ACE-induced angioedema. The efficacy of this intervention is controversial, but this is a safe and inexpensive therapy and may help while waiting for a more specific treatment. More on this at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29735174/

The diagnosis of ACE-inhibitor induced angioedema is made clinically, based on the presence of angioedema, without itching or urticaria, affecting a characteristic anatomic site, in a patient taking ACE inhibitors. The diagnosis is confirmed when the ACE inhibitor is discontinued and no further angioedema episodes occur. However, the impact of discontinuation may only be clear after several months, as some patients will have a small number of recurrent episodes, particularly in the first few months after the ACE inhibitor was discontinued.

Podcasts on angioedema:

References:

https://emcrit.org/pulmcrit/treatment-of-acei-induced-angioedema/

http://www.emdocs.net/emdocs-cases-angioedema-evaluation-and-management/

https://scghed.com/2013/11/cme-311013-angioedema-diagnosis-management/

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40521-019-0203-y

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5389952/

https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/networks/eci/clinical/clinical-resources/clinical-tools/angioedema