While some of the previous Ramblings from Red Shift have discussed rare medical conditions not often seen in Perth, a call from last week brought home how technology and access to information has improved patient care. Years ago when I started working in the ambulance service the initial training focussed on life-threatening medical conditions and serious trauma, with little time spent discussing minor injuries and non-life threatening or chronic medical conditions – which actually made up a huge part of the average presentations.

When the patient said they have a rare or not-so-common medical condition we had to hope that the patient could not only explain what it was, but also describe the correct management. Once handed over at the hospital (after hoping your treatment provided no harm to the patient’s condition), you then attempted to find a doctor or experienced nurse or paramedic who could describe the condition and how it should be treated, or take a visit to a library or medical bookstore. While we did have mobile phones – which were either the size of a brick or had a battery life measured in minutes – their most technologically advanced feature was the ability to play ‘Snake’.

Last week at 2:30 am we were called to a young female with left and right sided severe abdominal pain (both right and left lumbar and iliac regions), abdominal distension, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, pallor and dizziness on standing. The patient described her recent IVF (in vitro fertilisation) preparation procedures included egg harvesting the previous day and said that she had been warned that there was a risk for something called OHSS. After initial management with analgesia, anti-emetics and fluid, 60 seconds with Google provided everything we needed to know about OHSS (Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome), including assessing severity, risk factors and even Australian Government’s management guidelines.

Back to the Ramblings, so this week we are looking at OHSS – a serious complication of IVF caused by excessive stimulation of the ovaries. It happens when too many egg-containing follicles are produced and causes rather sudden enlargement of the ovaries and fluid retention in the abdomen. It is quite rare, but is a problem to some degree in 1 to 3 of every 100 treatment cycles and more frequently seen in women who have polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS).

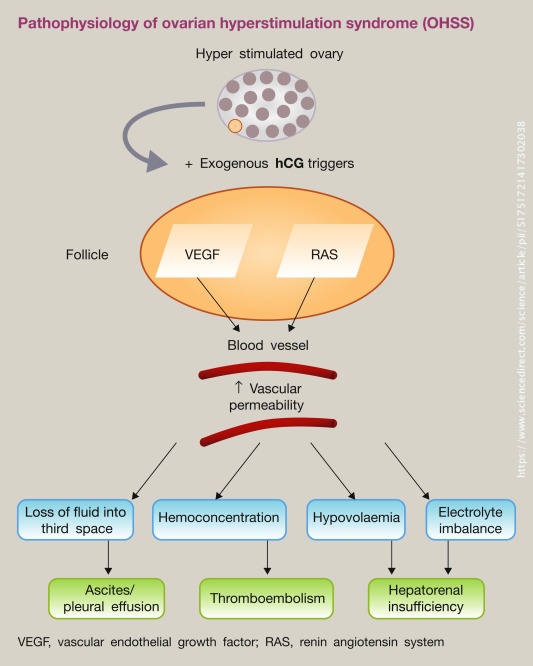

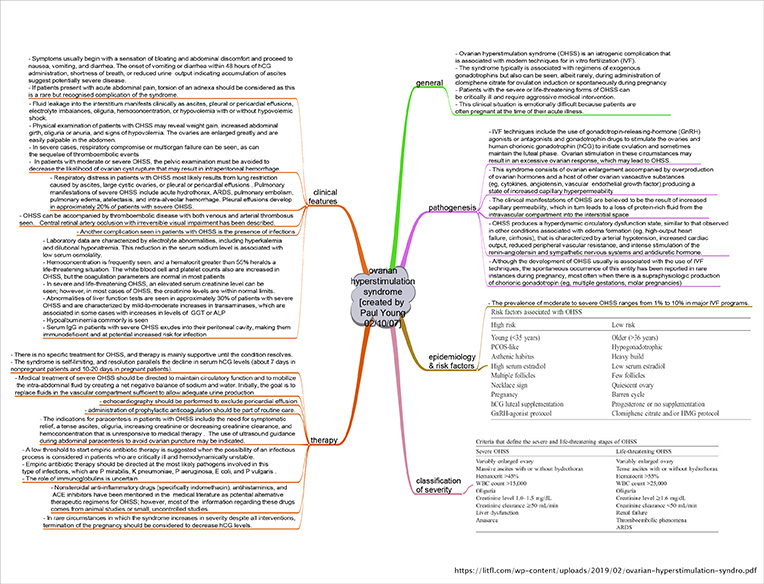

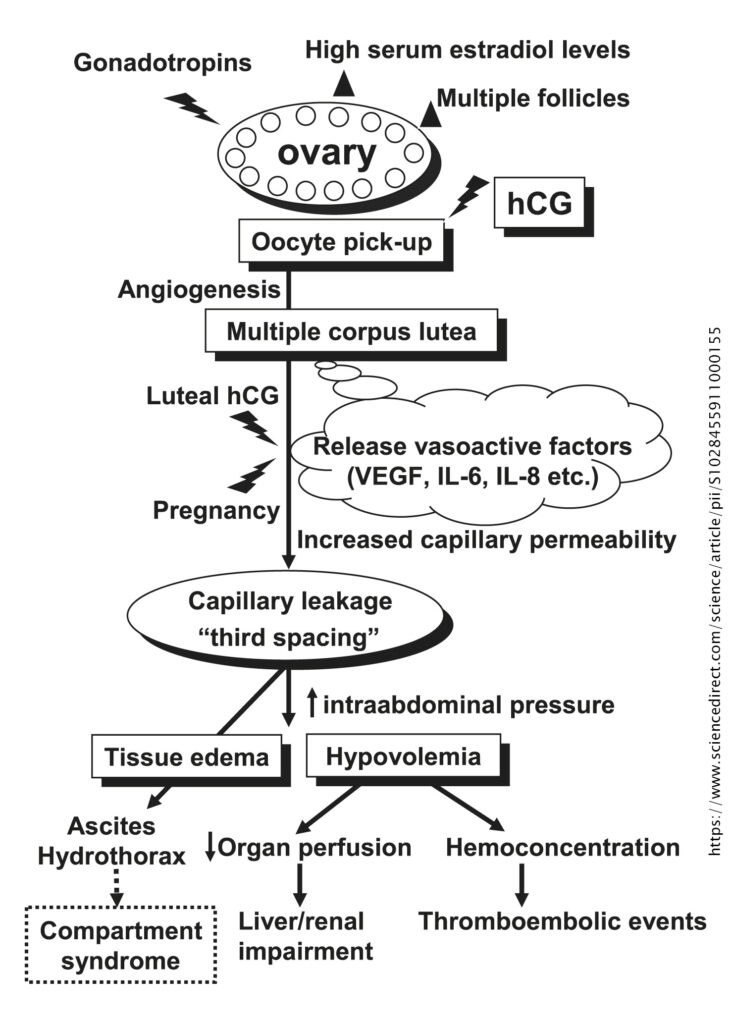

The syndrome is characterised by ovarian enlargement and a shift of fluid from the intravascular to the extravascular space due to increased capillary permeability. The pathophysiology of the syndrome is unclear. It has been suggested that exposure of hyperstimulated ovaries to hCG leads to the production of proinflammatory mediators such as VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) and cytokines. The proinflammatory medicators increase vascular permeability leading to accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal, pleural and rarely pericardial cavities, thus resulting in intravascular fluid depletion and haemoconcentration. The clinical presentation is usually between one to two weeks of the hCG ‘trigger’ injection, with later presentations usually associated with more prolonged and severe symptoms.

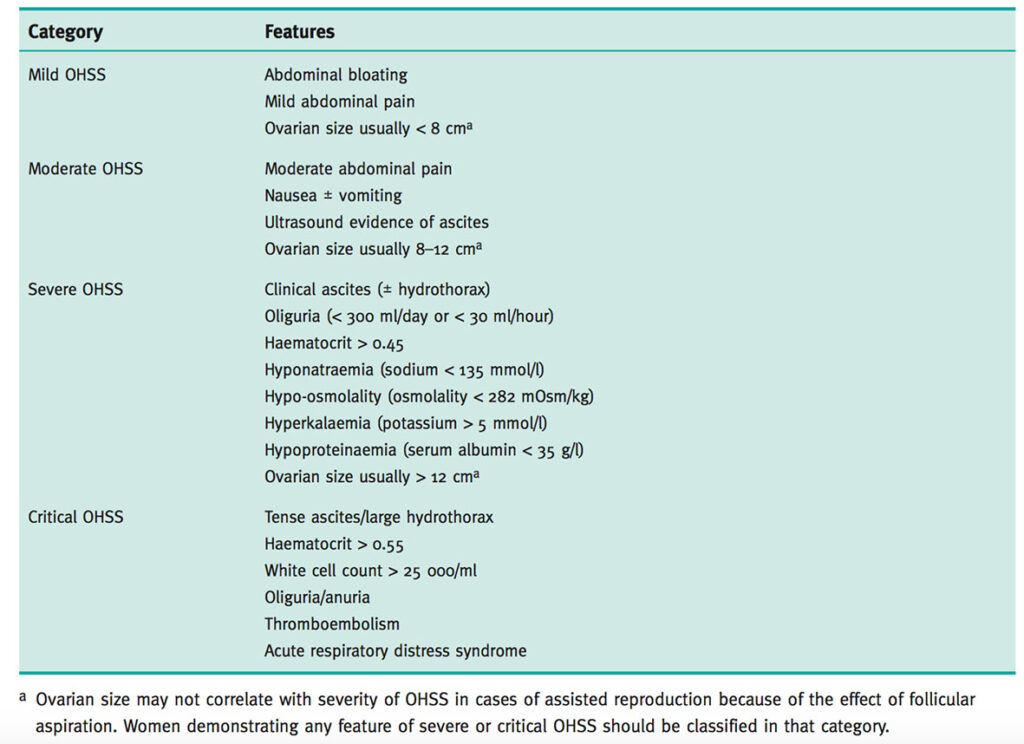

Common symptoms include abdominal bloating; abdominal pain and discomfort; nausea and vomiting, breathlessness (including an inability to lay flat or talk in full sentences); reduced urine output; leg swelling; vulval swelling and associated comorbidities such as thrombosis. The below table describes the classification of severity with associated symptoms. Rarely, OHSS may be associated with life-threatening complications, including renal failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), haemorrhage from ovarian rupture, and thromboembolism.

The aim of initial assessment is to establish the diagnosis and grade the severity of OHSS. Specific enquiry should be made for significant abdominal pain, shortness of breath or a subjective impression of reduced urine output. These symptoms may indicate severe OHSS and the occurrence of specific respiratory, renal or ovarian complications. The symptoms of OHSS are not specific and there are no diagnostic tests for the condition. Clinicians should also be vigilant for signs that the severity of OHSS is worsening. These include:

- increasing abdominal distension and pain;

- shortness of breath;

- tachycardia or hypotension;

- reduced urine output (less than 1000 ml/24 hours) or positive fluid balance (more than 1000 ml/24 hours);

- weight gain and increased abdominal girth; and

- increasing haematocrit (greater than 0.45).

Complications of OHSS include DVT (deep vein thrombosis); PE (pulmonary embolism); arterial thrombosis; internal jugular vein thrombosis and stroke (dizziness, neck pain and loss of vision); cerebral oedema; ovarian torsion; renal failure; ascites (abnormal build-up of fluid in the abdomen); and ileus (lack of movement somewhere in the intestines that leads to a build-up and potential obstruction).

Important differential diagnoses include pelvic infection, pelvic abscess, appendicitis, ovarian torsion or cyst rupture, bowel perforation and ectopic pregnancy. OHSS should not, therefore, be the ‘default diagnosis’ for women presenting with abdominal pain during fertility treatment.

Relief of abdominal pain and nausea forms an important part of the supportive care of women with OHSS. Analgesia with paracetamol and opiates is appropriate, while NSAIDs should be avoided as they may compromise renal function. Treatment is considered as supportive while waiting for the condition to resolve spontaneously while providing symptomatic relief; avoiding haemoconcentration; preventing thromboembolism and maintaining cardiorespiratory and renal function. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents should be avoided, as they may compromise renal function.

While we are not saying our patient definitely had OHSS, it was certainly a very valid differential diagnosis which did not form part of our initial consideration on attending the call. Vomiting, pain and shock can be symptoms associated with inflammation of any of the abdominal viscera and the absence of a fever, especially with recent paracetamol administration, does not help in the diagnosis. A focussed history, as in this patient, can aid in the development of differentials, and knowing that OHSS can require significant analgesia, volume replacement and specialist intervention promotes appropriate, timely management plans which anticipate condition progression.

Further reading:

Videos:

Podcast:

References:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1751721417302038

https://www.ajemjournal.com/article/S0735-6757(19)30329-8/pdf

https://litfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/ovarian-hyperstimulation-syndro.pdf

https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/green-top-guidelines/gtg_5_ohss.pdf

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/ajo.12389

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1028455911000155