Last week’s Ramblings looked at the fertilisation side of pregnancy, this week we will consider a condition occasionally seen after the pregnancy journey. During recent discussions with a paramedic regarding adapting to challenges faced when operating as a single responder, I was reminded of a colleague who was faced with managing a patient with a major secondary postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) in her first couple of shifts operating as a single responder – back in the time when first responder training just involved either being handed a set of keys or, if you were lucky, a couple of hours observing on a rapid response unit. Operating as a single responder can be stressful enough without adding in a seriously sick patient and administration of an infrequently used medication (Syntometrine®) without anyone to discuss or confirm details with.

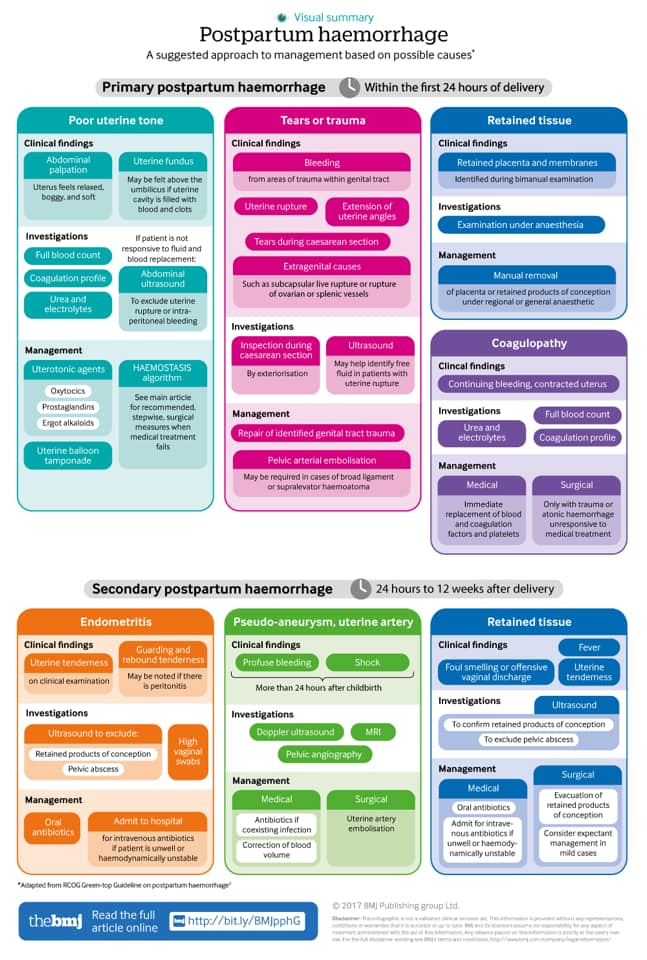

While primary PPH is traditionally defined as blood loss greater than or equal to 500 mL within 24 hours of the birth of a baby, secondary PPH occurs after 24 hours and up to 12 weeks postnatally. The overall incidence of secondary postpartum haemorrhage in the developed world has been reported as <1 to 2 per cent of pregnancies.

Secondary PPH is typically not as severe as primary PPH, but it can be just as alarming; in rare cases, however, bleeding can place the patient in a hemodynamically unstable situation. It should be noted that only 10 per cent of cases will experience a change of vital signs in the early onset of haemorrhage, with a significant number of cases having nonspecific clinical presentation due to occult haemorrhage and overlapping aetiologies (causes). A personal history of secondary PPH is a strong predictive factor; it has a recurrence rate of 20–25%.

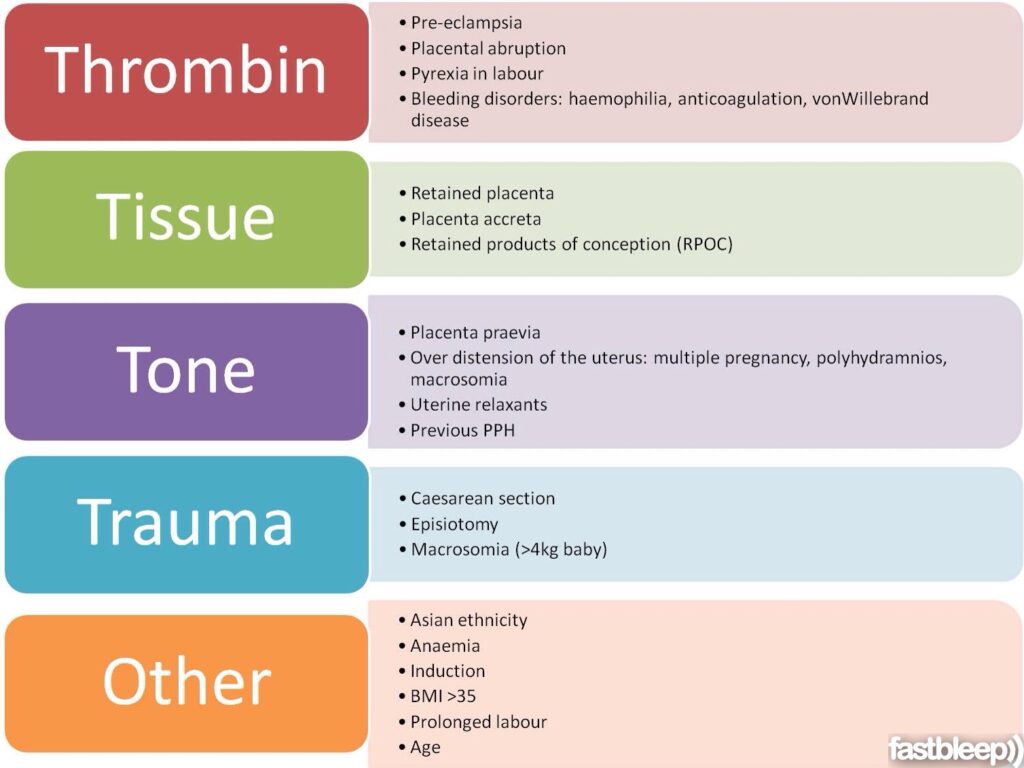

The pathogenesis is thought to be diffuse uterine atony or subinvolution of the placental site secondary to retained products of conception and / or infection in the uterus; however, the underlying cause is often not established. Usually uterine myometrial muscle bundles constrict to impede blood flow and large vessels thrombose to prevent haemorrhage at the detached placental site – incompetency of either of these processes will result in uterine atony. Additionally, if the patient has previously experienced blood loss from a primary PPH, anaemia may already be present and further complicate the issue. Causes of PPH can include:

- Abnormalities of placentation

- Subinvolution of the placental site (uterus does not return to normal size);

- Retained products of conception;

- Placenta accrete (placenta grows too deeply into the uterine wall).

- Infection

- Endometritis, myometritis, parametritis;

- Infection or dehiscence (separation) of caesarean scar.

- Pre-existing uterine disease

- Uterine fibroids (leiomyomata);

- Cervical neoplasm (rare);

- Cervical polyp;

- Uterine arteriovenous malformation (rare).

- Trauma

- Missed vaginal lacerations and haematomas e.g. ruptured vulval haematoma (may be associated with operative delivery).

- Coagulopathies

- Congenital haemorrhagic disorders (Von Willebrand’s disease, carriers of haemophilia A or B, factor XI deficiency)

- Use of anticoagulants (e.g. warfarin).

The four T’s mnemonic can be used to identify and address the four most common causes of PPH (uterine atony [Tone]; laceration, hematoma, inversion, rupture [Trauma]; retained tissue or invasive placenta [Tissue]; and coagulopathy [Thrombin]).

Secondary PPH is a clinical diagnosis of exclusion. Some post birth bleeding (lochia) may persist for several weeks – see below diagram. Bleeding may also represent the initial menstrual period after childbirth, (result of an anovulatory cycle – a menstrual cycle in which ovulation does not occur) and may be heavy, painful and prolonged. The time frame for secondary PPH also encompasses the period when contraception is often commenced and vaginal bleeding is a common side effect of hormonal contraception.

Vital signs may remain stable for a long time while occult bleeding and infection coexist. In addition, healthy women can lose up to one litre of blood before any change of vital signs is witnessed, leading to an abrupt turnaround of vital signs with rapid patient deterioration as haemorrhage evolves. By the time the combination of hypotension and tachycardia occurs, there has already been substantial blood loss that could represent 25% of total blood volume. Early recognition of symptomatology prior to becoming a full-blown emergency can help to prevent rapid decline.

The main symptom of secondary post-partum haemorrhage is excessive vaginal bleeding. The patient may complain of spotting on-and-off for days after her delivery, with an occasional gush of fresh blood. However, approximately 10% of cases will present with massive haemorrhage – and this can quickly lead to hypovolemic shock.

Additional clinical features will depend on the underlying cause. For example, women with endometritis may also present with fever/rigors, lower abdominal pain or foul smelling lochia (the normal discharge from the uterus following childbirth).

Symptoms of secondary postpartum haemorrhage include the following: * Fever and uterine tenderness if infection is present (typically lower uterine tenderness);

- Hypotension;

- Tachycardia;

- Tachypnea >22/minute;

- Decreased urine output;

- Lightheadedness;

- Paleness;

- Cold and clammy hands and feet;

- Syncope;

- Anaemia (severe anaemia is common prior to a secondary haemorrhage);

- Pain may or may not be present;

- Occult bleeding;

- Sudden bleeding after lochia has tapered off (possibly foul lochia).

It is important to recognise that even when no bleeding is visualised, if the clinical picture still fits a picture of blood loss, the assumption should be occult bleeding. Look for the signs that will help confirm occult bleeding such as a rigid abdomen, painful abdomen or bluish discoloration around the umbilicus (this is usually a late sign). While rigid abdomen is a typical tell-tale sign of occult bleed, fundal height itself may not necessarily reveal a rising uterus depending on the source of the bleed; bleeding could be totally retroperitoneal. Another misnomer is when the fundus palpates firm but the lower uterine segment is actually boggy. On abdominal examination, the patient may complain of lower abdominal tenderness (usually a sign of endometritis), or the uterus may still be high (sign of retained placenta).

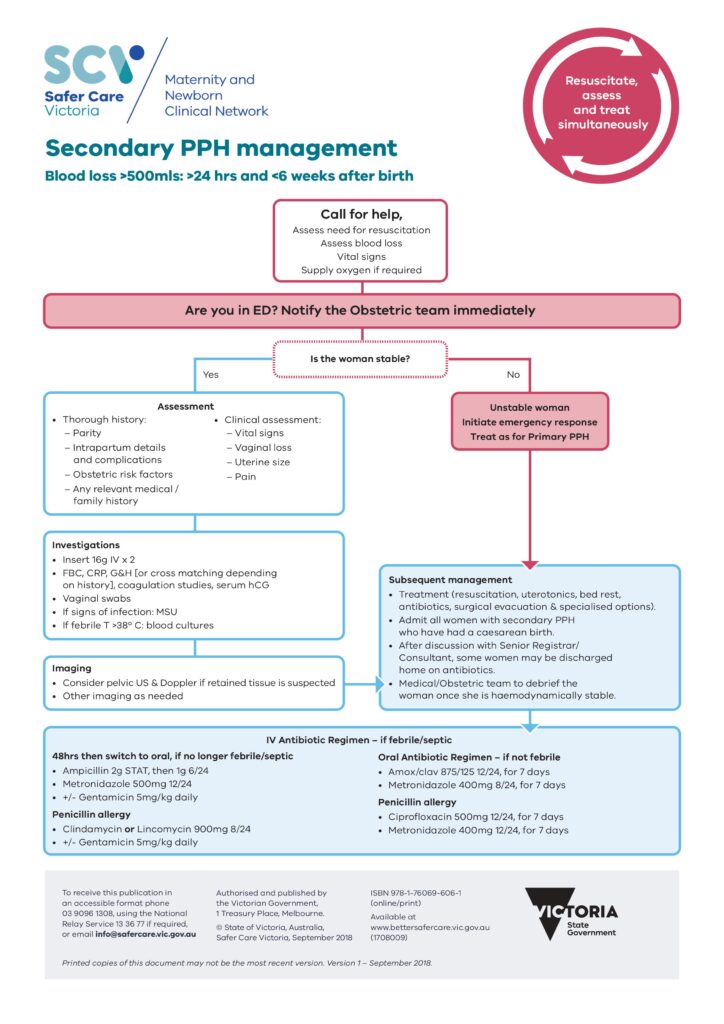

The treatment for secondary PPH should use the same guidelines as treatment for primary PPH – namely, attempt to achieve hemodynamic stability and identify the cause of bleeding. * Initiate resuscitation if required; * Assess blood loss (accumulative); and * If haemodynamically compromised, treat as for primary PPH. Evidence of shock suggests severe sepsis requiring urgent intervention.

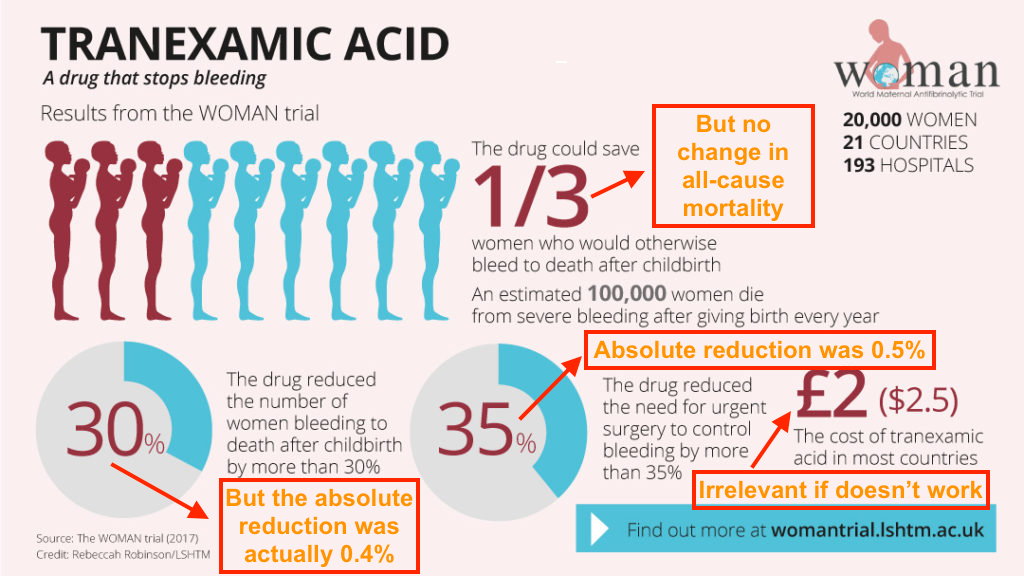

The “WOMAN” Trial claimed to demonstrate the efficacy of the administration of 1g of tranexamic acid intravenously with a clinical diagnosis of PPH. The dose was repeated after 30 minutes if bleeding was persistent. The authors concluded that: “Tranexamic acid reduces death due to bleeding in women with post-partum haemorrhage with no adverse effects. When used as a treatment for postpartum haemorrhage, tranexamic acid should be given as soon as possible after bleeding onset.” Broome GP Casey Parker @ Broome Docs describes his views on the WOMAN trial here:

Queensland Ambulance Services’ CPG for secondary PPH can be read here:

https://www.ambulance.qld.gov.au/docs/clinical/cpg/CPG_Secondary%20postpartum%20haemorrhage.pdf

Hospital guidelines for secondary PPH and PPH in general:

For the listeners amongst you, a podcast on PPH can be found here:

Documented case study for secondary PPH can be found here:

References:

https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/suppl/2017/09/27/bmj.j3875.DC1/chae036081.wi.pdf

https://www.glowm.com/pdf/PPH_2nd_edn_Chap-56.pdf

https://www.ambulance.qld.gov.au/docs/clinical/cpg/CPG_Secondary%20postpartum%20haemorrhage.pdf

https://www.bettersafercare.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-11/Secondary%20PPH.pdf

https://www.rch.org.au/piper/guidelines/Secondary_postpartum_haemorrhage/

https://blog.thesullivangroup.com/case-recognizing-secondary-postpartum-hemorrhage

https://blog.thesullivangroup.com/understanding-secondary-postpartum-hemorrhage

https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/0401/p442.html

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19625573/

https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/140136/g-pph.pdf